Azito Energie, Power, Côte d’Ivoire

In Azito Village, Côte d’Ivoire, multiple CSCs served to engage community and company stakeholders, build consensus on projects of importance, and boost development results.

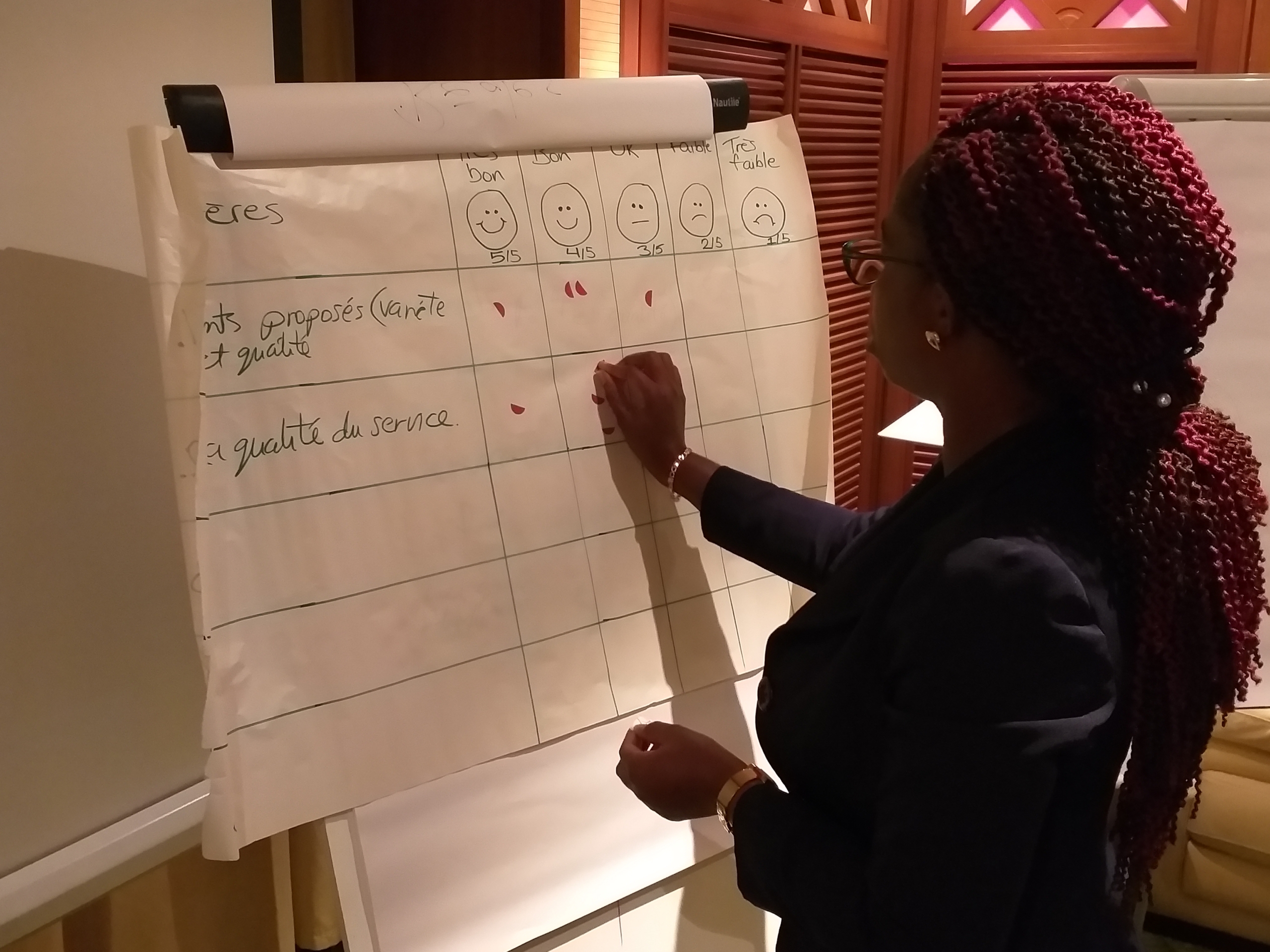

Photo by IFC

Photo by IFC

The Azito Energie Thermal Power Plant, located in Azito Village, supplies 35 percent of Côte d’Ivoire’s energy needs. An IFC client, Azito has made use of the CSC process multiple times, because of the value of tool in engaging all stakeholder groups within the village to ensure the effectiveness of the company’s support for the community.

First CSC identifies community development priorities

The first CSC was initiated by Azito and brought to the table a range of community representatives, along with village leaders and company executives, with the goal of assessing the effectiveness of the company’s social responsibility program. The process resulted in the identification of priority community development projects that Azito could integrate into its revised social responsibility program. In parallel, IFC worked with Azito village to set up a participatory governance structure to oversee the €3 million in funds provided by the company as compensation for the lease of the village’s land, aimed at supporting additional priority local development projects.

Among the examples of successful local development projects: the construction of a mixed-use development in nearby Abidjan, featuring office, retail, and residential components. Today, the village earns about $100,000 annually in lease income from the project, funds that flows back into the community investment fund and support additional development efforts.

Other projects included upgrades to the local health center—deemed a critical need since the CSC took place at the height of the covid-19 pandemic. In addition, CSC participants prioritized

the creation of a training program so community members gain the skills needed to qualify for jobs within the company’s value chain as well as build their own businesses. The program has placed particular emphasis on women and youth –another first for the village. An offshoot of this project, a business cooperative for women, gave female community members the opportunity to work together to generate income for their families.

Second CSC reviews progress

The second CSC, also initiated by the company, revisited these community investments, to assess progress and identify areas where changes might be needed. This CSC targeted the village’s all-male leadership, with the goal of demonstrating the value of participatory processes in good governance. “The idea was to reflect on what had been done thus far and gather feedback from all the various stakeholders and implementation partners,” explains IFC’s Joel Colomb, who was involved in all of the Azito CSCs. “We engaged at the chieftaincy level—the village’s highest leadership—and we reviewed all the priority projects and the implementation strategy across all activities.”

During this CSC process, which took place as the pandemic wound down, several issues came to light, resulting in adjustments to the community’s investment strategy. For example, in reviewing results from the health center upgrades, CSC participants noted that with the covid outbreak mostly over, there was a greater need for expanded rehabilitation facilities rather than for acute care. An important outcome of the CSC was a revised work program to expand the health center’s rehab offerings.

A second outcome involved changes in the operations of the women’s cooperative—also related to the pandemic’s end. With country borders reopened and trade resuming, there were new business opportunities for women. A follow-on strategy workshop with cooperative members, village leaders, and company representatives identified a promising business venture—a fish market. Subsequently, the IFC team helped to design business plan to get the new venture underway.

Third CSC assesses leadership and governance

The third CSC assessed the work of the village leadership and their progress in supporting inclusive community development. It included company representatives and community members, who shared their opinions on what should be done to improve community work.

“This took place at a time when there was a new generation of younger leaders coming to power, who were more open to inclusion,” Colomb explains. “We used this as an opportunity to facilitate the transition to the new generation.” He notes that the new leaders were eager to engage in the CSC process—in large part because they had benefited from the earlier CSCs, which had given them a voice in community affairs that they previously did not have. “They were very aware that one of the reasons they were able to transition into power was because of the CSC process,” Colomb says.

Among other positive outcomes, the third CSC resulted in revised plans for the women’s cooperative, reflecting the initial success of the fish market venture. The new strategy enabled the cooperative to secure $100,000 to finance the purchase of new equipment.

Colomb adds that a remarkable culture change took place between the time of the first CSC and the third. “At first, having a woman or young people in a meeting wasn’t something that happened.” Now it is common for women and young people to attend community meetings. “And they don’t just sit there quietly. They readily share their opinions and perspectives,” he says.

The IFC team completed their work with Azito Village by training community members and company representatives to become CSC facilitators. According to Colomb: “We wanted them to use the CSC tool themselves so they can replicate the process.”

Takeaways from the multiple Azito Village CSCs

- CSC is a powerful tool to gather people who don’t usually talk to each other. It provides a forum in which everyone has a voice and each voice is equally important. And it brings people together to share a common vision.

- CSC opens lines of communication and helps dispel misperceptions. Colomb recalls that during the first CSC, there was significant community dissatisfaction with the company over the lack of job opportunities. But it wasn’t that the company was purposely excluding local workers; rather, the plant did not need much staff to run it, since it is mostly automated. “In the CSC action plan, we took several steps to help community members understand the realities of operating a power plant, like taking a field trip to the plant to show them how few people actually work there,” Colomb says.

- The CSC process can be used in a wide variety of circumstances but buy-in is critical. Since the completion of the IFC engagement, Colomb has heard that Azito Village leaders have used the tool to address different issues within various community groups. And that is the point, he says. “At the end of the day, for it to work and have impact, they have to own the process themselves.”

Want to implement a CSC?

THE COMMUNITY SCORECARD IS SUPPORTED BY: